The Truth About Lactic Acid

- December 13, 2018

- Success Coach

- Coaching

- No Comments

I have recently noticed one of my coached riders mention lactate in there comments on Training Peaks a lot. Comments like “at the start of the session could still feel the lactate from yesterdays session” or “took a while to warm up and get rid of the lactate”. So I thought it would be good to right a short blog on the truth about lactate acid.

You end your day content that the day’s 90 minute turbo session has brought you one step closer to your season’s goals. Your body audit reveals all is good as you look forward to a decent night’s sleep ahead of another strong session tomorrow. Fast-forward to the next morning and your legs feel like lead. “Damn, lactic acid has got me again…” you think. Yes we have all been lead to believe that lactic acid is what the cause of our legs aching are.

Despite it’s bad-boy reputation, lactate is a beneficial substance for the body during exercise. It can be used to create more energy so that you can continue training or racing.

So while many people think post exercise soreness or DOMS (delayed onset of muscle-soreness) derives from lactic acid (or lactate), this simply isn’t true. The feeling you experience from lactic acid subsides within 30 minutes and any residual fatigue and pain you feel the following day is more to do with muscle damage.

So how did lactic acid get such a bad reputation and the blame for all those sore legs? Well it is all down to a Nobel Prize winning biochemist called Otto Meyerhof. During one of his experiments, Meyerhof cut a frog in half and put its legs in a jar. It’s muscles had no circulation and no source of oxygen or energy. Meyerhof then sent electric shocks through the frog’s legs to make the muscles contract and then discovered they were bathed in lactic acid. As a result, the theory arose that a lack of oxygen reaching working muscles causes the accumulation of lactic acid, which leads to fatigue, a theory that proved to be incorrect although Meyerhof was right to conclude that lactic acid is created when oxygen isn’t present.

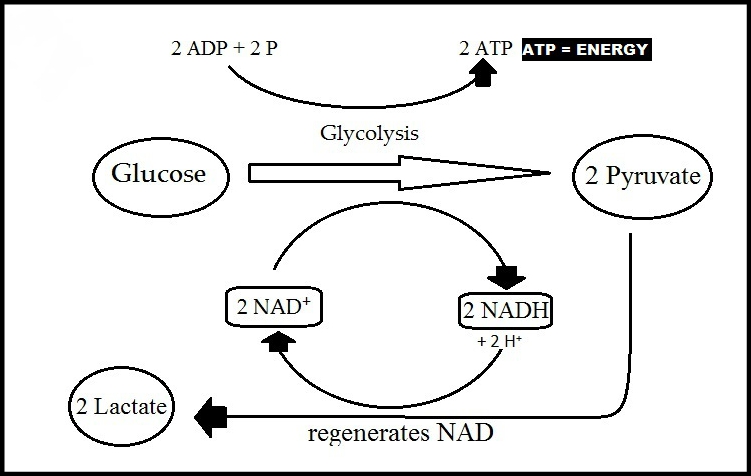

Before carbohydrates can be turned into energy they must be converted into pyruvate. Pyruvate then has two possible next steps, 1 it either follows the aerobic (with oxygen) pathway to produce more energy or 2 if it’s unable to enter the pathway easily it is converted into lactate. With oxygen present, pyruvate is broken down to create energy in the mitochondria of your muscle cells. If oxygen isn’t present (when for example, your climbing a steep hill and your body can’t absorb oxygen quick enough to breakdown fuel) your body creates energy via glycolysis. This takes place within a liquid in your body’s cells, called cytosol. Lactate is a byproduct of creating energy anaerobically within the cytosol and historically it is this that has been associated with fatigue.

Lactate isn’t the problem. The problem is when lactate is produced, it is done so with hydrogen ions and it is these that cause your muscle fatigue and not the lactate. So next time you are trying to escape the pack with a fellow rider, how’s about shouting across to ask him how many ions he has in his legs and then laugh at the puzzled look on his face. Hydrogen ions raise blood and muscle acidity levels, blocking nerve signals from the brain to the muscle fibres. Over time, your limbs begin to feel heavy and you naturally slow down to allow more oxygen to the the working muscles. So next time you are trying to escape the pack with a fellow rider, how’s about shouting across to ask him how many ions he has in his legs and then laugh at the puzzled look on his face.

Not only does lactate not cause the ‘burn’, once you’ve slowed down and let oxygen flood your muscles, your mitochondria burn lactate to produce energy. One of the key pieces of research into this was conducted by George Brooks, professor of integrative biology at the University of California. He discovered that endurance training reduces blood levels of lactate, even while cells continue coproduce it, inferring that lactate is shuttled to the mitochondria to be reused.

Essentially, lactate acts as an intermediary between aerobic and anaerobic metabolism with further research showing that up to 75% of lactate produced is used for fuel. And when the amount created initially is greater than the energy being produced aerobically, that’s your anaerobic threshold (AT).

Measuring lactate levels in your blood is a convenient way of estimating how much hydrogen is in your body. The more intense the workout, the more lactate is released into your body, and the more hydrogen ions interfere with muscle contractions.

The anaerobic threshold varies from person to person with untrained individuals having a low AT (around 55% of Vo2 max) compared to elite athletes whose AT will register around 80-90% of Vo2 max. The higher you’re AT, the higher the intensity and duration you can race at, and this is why all coaches will prescribe sessions designed to raise it.

It might feel painful but, by training at AT, your system becomes more efficient at using lactate as fuel. One of the reasons for this is that lactate production stimulates a process called ‘mitochondrial biogenesis’ once exercise has ceased. Essentially this increases mitochondria concentration within the cells, which is one of the major adaptations you’re looking for to improve endurance performance. It seems paradoxical that lactate, a byproduct of the anaerobic system, can boost your aerobic system but it’s true, and it’s why interval training is so important.

So what can you take away from this? Firstly, lactate is your friend. It provides energy, doesn’t cause fatigue and has no relationship with muscle soreness. Hydrogen ions are the problem but you can starve off their effects by integrating intervals into your training. By mixing bursts of higher intensity efforts with rest periods, you’re constantly raising lactate levels rather than simply pushing on for longer and stopping sooner, which would ultimately mean less time training at your AT.

Leave a Comment cancel

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.